THE GUARDIAN (6/6/2024)

Sitting in the shade of an olive tree in the valley of Ein Qiniya, northwest of Ramallah, wildlife photographer Mohamad Shuaibi starts to enumerate the birds he can spot that spring morning. Swifts and swallows flit and swoop around, a short-toed eagle hovers in the distance, a jay sits perched on an olive branch and a kestrel returns to its nest in the limestone cliffs.

He also starts counting the times he has been stopped and questioned by Israeli soldiers or police out in the field with his zoom camera. “I was detained four times already since October, and each time was worse,” he says. He now avoids going out a certain times. “To watch birds we need to go out very early in the morning. But most of the [Israeli] military operations are in the early hours, so you can be shot if you’re out around this time.”

Spring sees millions of birds fly over Palestine, part of the world’s second-busiest corridor for bird migration. Positioned between Africa, Europe and Asia, the region is a bottleneck and an important stopover for hundreds of migratory species travelling between their wintering grounds and breeding sites.

“The migration hasn’t stopped,” says Shuaibi, who works as a shop assistant and took up birdwatching as a hobby about a decade ago. “These birds, despite the war, they are still coming. And it gives us hope.”

Over the years he has struggled with the lack of funds, the difficulty of getting equipment, and restrictions of movement imposed on Palestinians living in the occupied West Bank. But recent months have been the most difficult and dangerous he can remember.

On the same April day that Shuaibi sat under the olive tree listening to birdsong, around 20 kilometres away, hundreds of Israeli settlers descended the hills surrounding Palestinian villages east of Ramallah after a 14-year-old boy went missing from a nearby settlement. They shot residents, torched houses and cars, and slaughtered animals. The two-day rampage left two Palestinians dead, dozens injured and widespread destruction.

Since October 7, when Hamas-led fighters broke through Gaza’s fences killing 1139 people and taking approximately 250 hostages, at least 505 Palestinians have been killed in the West Bank by Israeli soldiers or settlers, according to the UN, and entire villages have been displaced.

With the world’s attention focused on Gaza, escalating settler violence and closures have kept Palestinians in the West Bank living in fear restricted to their homes. Birding – which involves roaming outdoors with a camera or binoculars – has become a high-risk activity. But raising their heads high, some Palestinians are defying the dangers to admire the birds filling the sky.

Birds feature prominently in Palestinian folktales, proverbs, art and poetry. Saed Shomaly, an ecotourism guide and founder of the Palestine Society for Environment and Sustainable Development, has noticed an increased interest in birding in recent years.

“We have four biogeographical regions which makes this area very rich in biodiversity,” says Shomaly, who worked on projects to conserve Bethlehem’s swifts and the Jordan Valley’s barn owls. He has counted 375 bird species in the West Bank’s varied habitats, ranging from wooded mountains and rocky slopes to the cliffs and desert plateaux of the Dead Sea.

“Last spring I organised a race for birdwatchers in Jenin, and we had 21 Palestinians participating. They came from as far as the Naqab desert and the Galilee to join,” says Shomaly. “But this year it was impossible to gather.”

As a Palestinian who has lived his entire life under Israeli occupation, Shomaly has always had to tread carefully while hiking across the West Bank with his binoculars and avoid venturing out too close to Israeli settlements or military areas declared ‘firing zones’.

Since October, the restrictions imposed on Palestinians have become even more suffocating. Israeli forces and settlers have erected 114 new checkpoints, roadblocks and gates in the West Bank, where there are now 759 obstacles according to the UN.

“When we want to breathe we go out to the nature reserves,” says Shomaly, who worked on a website to share information about nature reserves and bird habitats in the West Bank and Gaza. “But the settlers are taking them away from us. We can’t enter many of them any more. They want to suffocate us,” he says.

Shomaly used to love hiking in the al-Auja nature reserve, an oasis in the Jordan Valley, but has been unable to access the reserve since October.

Birds are still coming

Yet Palestinian birders are determined to continue their searches for joy and beauty. “I have a lot of love in me, a passion for birds, for nature,” says Shomaly. “And so I continue to go out to watch birds, to study them, to publish information about them. We have to preserve this heritage for future generations.”

“Sometimes I go out wondering whether I will get back or not. But if I die, I worked for Palestine – and I worked for the birds.”

Despite the risks, Shuaibi also carries on documenting wildlife. His ambition is to organise an exhibition to show the biodiversity of Palestine.

“I want to show the world this is not just a country of war. It’s not just death, bombings, and killings. There are people who are interested in wildlife, even when nothing is available to them,” he says. “There is life here. And we love life.”

Israeli restrictions won’t stop the birds from coming. “Prisoners feel hope when they see the birds,” says Ikram Quttainh, a birdwatcher from Jerusalem, as birds can fly over the barbed wire and barriers built to confine and segregate Palestinians. “They remind us that freedom and beauty still exist, even in the harshest conditions.”

Birds continue soaring over Gaza, even as Israel expands its offensive that has killed more than 36,000 Palestinians, mostly children and women, and displaced 1.7 million. Israeli attacks have resulted in catastrophic destruction and have been described as genocide and “ecocide”.

“Watching birds and wildlife gave us much comfort from the terror of war, displacement, and the tragedies in Gaza,” say birdwatchers Lara and Mandy Sirdah in audio messages sent from Deir al-Balah, in the centre of the strip.

Forced to leave their homes in the north after Israeli evacuation orders, the twin sisters were not allowed to take their equipment with them, but are still birdwatching and publishing photos of bee-eaters and bulbuls. So far, they have listed 39 resident and migrating species they spotted over the last months of displacement.

For the twins, the large flocks of birds flying over Gaza in their northward migration have been a source of solace. “When we saw the birds flying over us from the south we hoped that like the birds we can also return north to our homes when the war ends,” they say.

The chance to breathe clean air

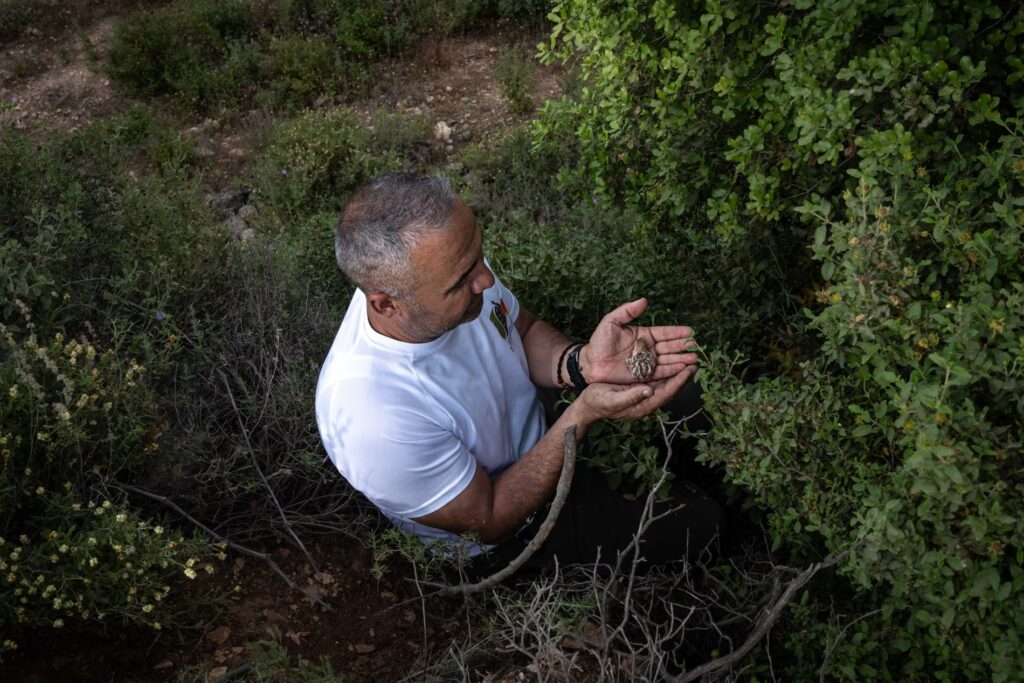

Gathering on a wooded hilltop overlooking terraces of olive trees and vineyards, a group of 9th-grade girls from the Aida refugee camp watch attentively as Michael Farhoud, a researcher at the Environmental Education Centre (EEC) in Beit Jala, holds a chiffchaff in his hand.

The tiny olive-brown warbler was caught in nets earlier that morning. As Farhoud measures the bird and attaches a ring to its tiny leg, he explains to the schoolgirls how ringing tracks birds’ movements.

Established in 1986, the centre features a botanical garden, a bird recovery centre and a natural history museum. It has opened bird monitoring and ringing stations across the West Bank and publishes studies on local biodiversity. “We want to encourage people to care for life and for biodiversity, and to defend climate and environmental justice,” says Simon Awad, EEC’s director.

For months, access to the centre was restricted by Israeli closures. Awad picks up his phone to show footage of a young Palestinian man being shot dead by an Israeli soldier when trying to remove a roadblock to help a car drive through. It was filmed by security cameras outside the botanical garden last December, just a few metres from where the students stood with binoculars in hand marvelling at storks soaring above them

15-year-old Lamis Al-Harithi says she loves watching migrating birds. But her favourite bird is the bright coloured Palestine sunbird, a resident species. “I love it because it’s a symbol of Palestine,” she says. With a long and curved beak adapted to extract nectar from flowers and stunning iridescent blue feathers, it was declared the national bird in 2015. “The sunbird doesn’t migrate. It stays here all year,” she says as her classmates nod.

Their Unrwa school, established for Palestinian refugees expelled by Israel, is cut off by the separation wall and surrounded by Israeli settlements considered illegal under international law. A study published by the University of California in 2018 found residents of Aida refugee camp were among the most exposed to teargas in the world.

The field trip allows children to breathe clean air under oak and pine trees. When it is time to release the chiffchaff so it can resume its journey north, the girls shriek with joy. The birds are free to go wherever they want, they say. And the chiffchaff flies away.

Photos by Samar Hazboun and Mohamad Shuaibi

The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/article/2024/jun/06/palestine-gaza-west-bank-nature-birds-birdwatching-aoe